What’s In a Name?

May 19, 2012

Names are powerful. Simply changing the name of something can have drastic effects. A name is something concrete that we can latch onto in our thoughts. Without a name, we fumble around. Without a name, a concept blurs. We can sharpen that concept by adding more and more descriptors. Yet, this becomes cumbersome as the descriptors mount. A name embeds all of these descriptors and brings clarity to our thoughts. Consider this exchange:

Your friend: I just saw the weirdest car!

You: Weird how?

Your friend: It was real low down.

You: So?

Your friend: It was a super low, classic car. But, get this, it could hop up and down too!

You: Ah, man. That’s just a lowrider!

You can’t picture a weird car as you’ve seen plenty of weird cars, so the concept is initially very fuzzy. As you get more and more details, the image starts to take form. Once you name it, you have a solid image of it. But you have to be careful. The word “lowrider” not only describes that car, but the driver. It’s a whole culture, and maybe that car and driver are not part of that culture. Using “lowrider” means that you are on one level or another buying into all the assumptions implicit in that term.

This is exploited all the time. To name one easy example, take the “pro-life” moniker. Instead of calling themselves anti-abortionists, the pro-life group has linked themselves to all of human life by embeding the word “life” in their name. They force you think of their cause as defending all of the sanctity of life, which is a very just, noble cause.

Advertising loves to do this. By linking a product name with good traits, whenever you think of that product you associate it with those traits. Will beer really get you into a group sex? Of course it won’t! But if you are exposed to the commercial enough, you’ll link the two on some level. Next time you think of beer, you may think about how it will help you get laid.

Fittingly, if you are aware of this effect you can counteract it and use it for your own ends. In reading, “Universal Principles of Design” I realized just how much advertising uses these design principles. Nearly all of the principles have citations in psychology literature, so by learning these principles you can influence the thoughts of others and be on guard for those trying to do the same to you.

The picture above helps explain why companies seek to expose you countless times to their logo and name. I always thought it was silly that companies would print their name on a pen. A pen? Really, would just putting your name on a pen make me buy a product from you? This principle suggests that it would. Especially when you learn about the exposure effect, which is that subjects exposed to a neutral stimuli will grow to like the stimuli. So by simply exposing us to a corporate logo over and over again, we grow to like that logo. And for good measure, throw in some classical conditioning, where a stimulus is associated with an unconscious physical or emotional response. The aforementioned commercial conditions us to like the beer by associated it with fantastic sex. These three principles make it so that when we walk down the beer aisle, we recognize the brand, we unconsciously like it, and then we buy it. These principles go a longways towards explaining why our lives are so saturated with ads.

I would encourage you to check out the book. It’s really gorgeous and well done. There are a hundred concepts, and I only knew maybe fifteen of them by name. I knew about half of them on some vague level, but now that I have a name for them I can exploit them and be on guard.

I’d like to finish this with one last example on the power of names and their baggage. In my lab group, we come up with models that we name. We usual name them on the day they are finished. So when we finished a model on the fifth of November, it was christened Guy Fawkes. Clearly, we should have thought a bit harder as our British sponsors are less than amused!

Aside

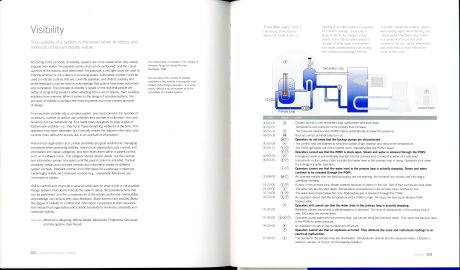

Sorry, but as a chemical engineer, I wanted to share the above spread. In one of my classes, someone presented on 3 Mile Island. He did a terrible job, and I had forever been confused. This nicely summarizes the events of that day and explains how visibility could have prevented the near disaster. The book also includes factor of safety as a principle and cites the Challenger disaster as an example of what not to do. Clearly, a little bit of good design can stave off serious problems.